"You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete."

BUckminster Fuller

Systems Theorist

- Date

DIFFERENT MODELS TO HELP US UNDERSTAND MOTIVATION, VALUES AND NEEDS

posted in Values

Adam Kreek

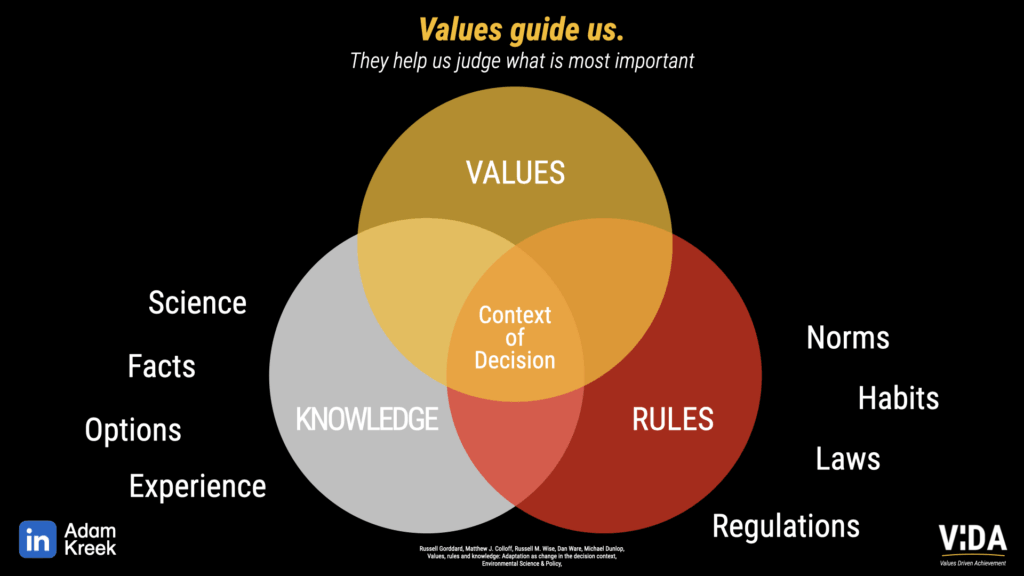

Values are the first step of logic we use to justify our feelings and subconscious motivators. Many scholars have looked to classify values, and look for social trends that we can use to create a better world.

ViDA Definition of Values:

Values are the internal traits or states we bring to every action and decision. They are not "things we achieve" (like wealth or family) but qualities we embody, such as:

- Authenticity: Being true to oneself.

- Discipline: Consistent effort toward goals.

- Compassion: A deep concern for others.

- Resilience: The ability to recover and thrive in the face of adversity.

When understood through the ViDA framework, values become tools for clarity, decision-making, and action, ensuring that our lives are aligned with who we are at our core.

Values are the innate, deeply held character traits or states that are most important to us in life. They guide and motivate our actions, behaviours, and decisions by reflecting the core essence of who we are and who we strive to be. Values are not external outcomes or entities like family or wealth; instead, they are the internal traits that influence how we engage with those aspects of life.

Key Principles of ViDA Values:

- Character Traits and States:

Values are qualities like honesty, courage, creativity, or kindness—core elements of who we are or how we act when we are most aligned. They are not tangible things or roles but feelings or a values state that drive everything we do. - Action-Oriented:

Values fuel decisions and actions. For example, a person who values growth will seek out opportunities to learn and evolve, even in challenging circumstances. - Alignment Equals Fulfillment:

When we act in accordance with our values, we feel fulfilled, energized and authentic. Misalignment—when our actions contradict our values—leads to dissatisfaction, stress, and even a sense of violation. - Intrinsic Drivers:

Values are not tied to external achievements or roles but to internal states. For example:- Courage (value) might drive someone to take a stand for a cause.

- Generosity (value) influences how someone helps others, regardless of the context.

- Separate from Goals or Terminal Values:

Terminal values like "family," "success," or "community" are outcomes or destinations. The values tied to these could be connection, dedication, or service, which are the traits that guide how one engages with those goals or outcomes.

When we understand values, and know our values, we make better decisions and have better relationships.

Below is a summary of a number of values models to help you better understand this esoteric concept with links for you to explore.

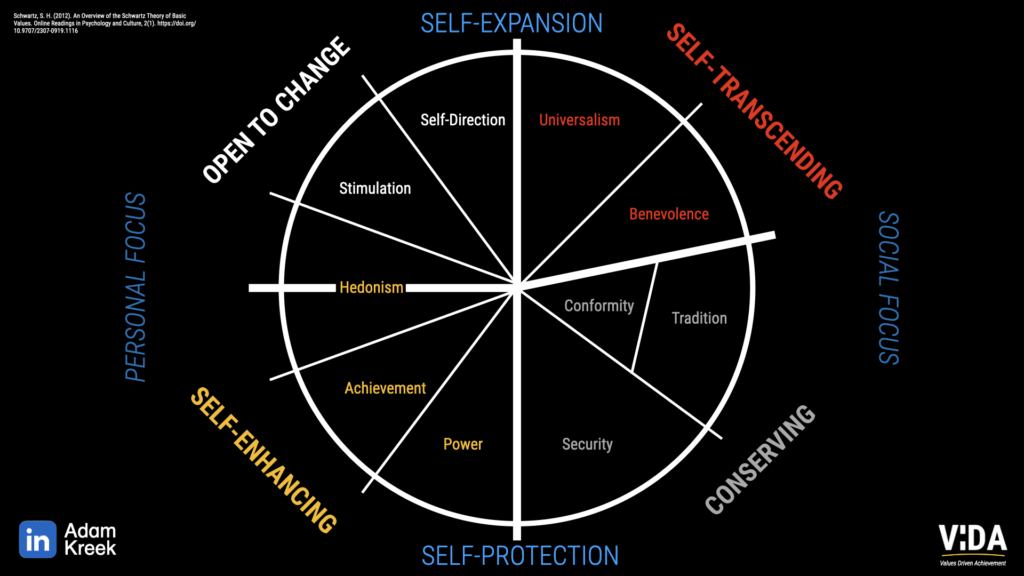

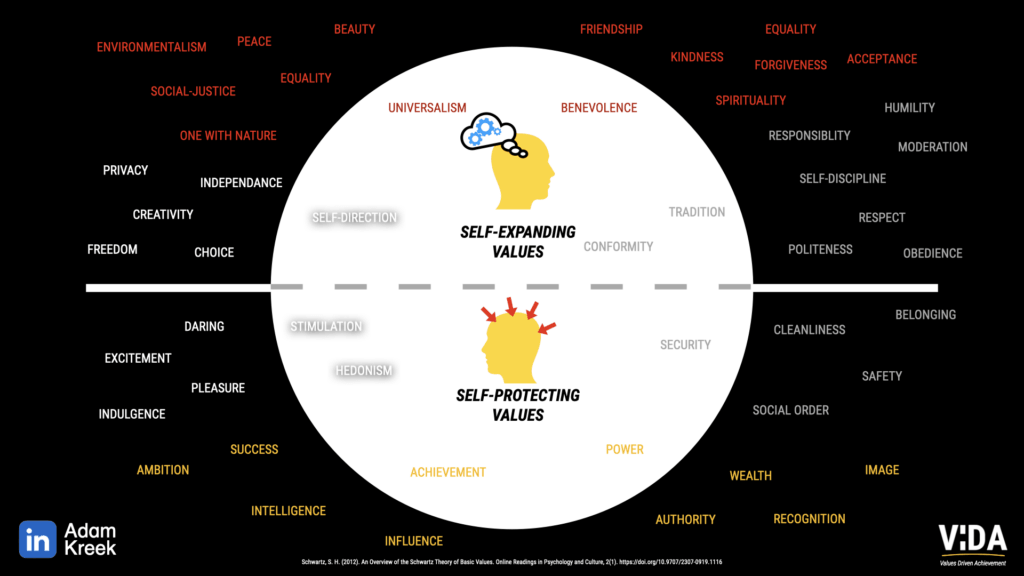

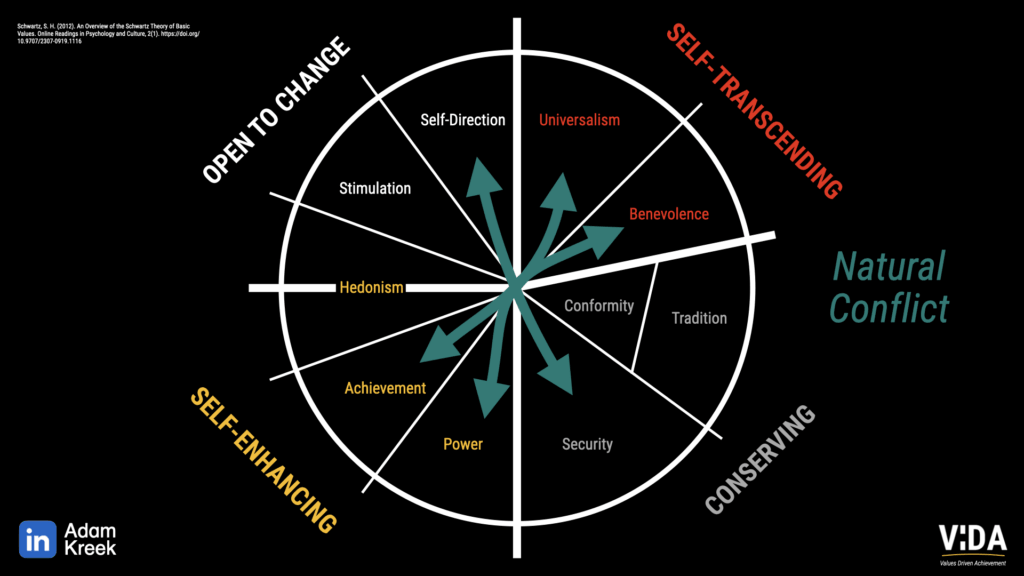

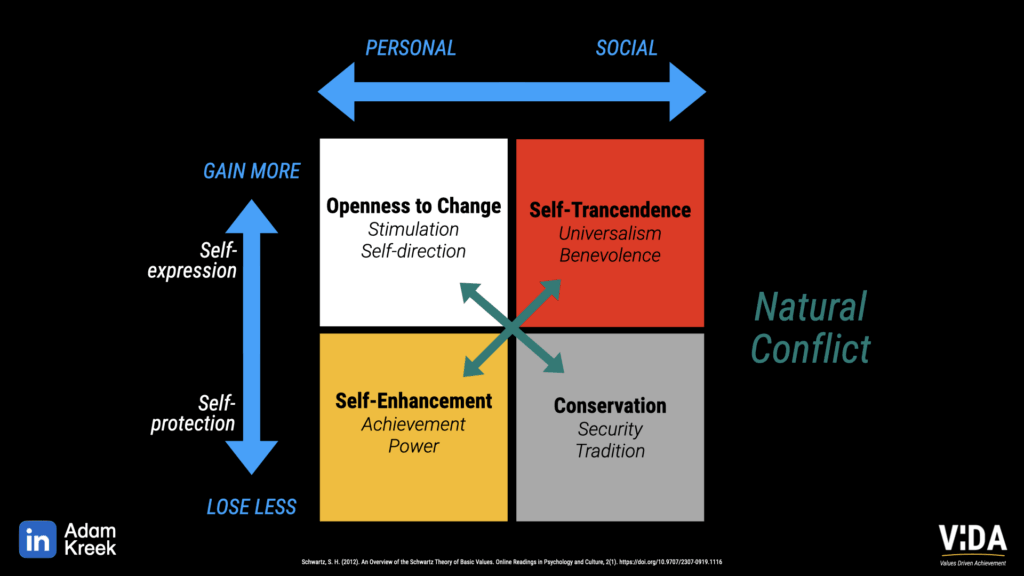

The Theory of Basic Human Values

Social psychologist Shalom H. Schwartz developed a list of human values that all cultures recognize. His list consists of 10 core values which can be grouped in 4 categories. According to the ViDA definition of values, these are categories of core values.

Openness to change

- Self-Direction (Freedom of thought and action)

- Stimulation (Excitement, novelty, and change)

Self-Enhancement

- Hedonism (Pleasure or sensuous gratification)

- Achievement (Success according to social standards)

- Power (Control over resources and people)

Conservation

- Security (Safety, stability and order)

- Conformity (Adherence to informal and formal social expectations)

- Tradition (Maintaining cultural, family, religious customs)

Self-Transcendence

- Benevolence (Promoting the welfare of your community)

- Universalism (Appreciation and protection of all people and nature)

Schwartz has collaborated with hundreds of researchers who have applied his theories and methods for measuring values in more than 80 countries. His research has been published internationally in journals of social psychology, cross-cultural psychology, developmental psychology, political psychology, sociology, education, law, and economics.

The Features of Values, defined by Schwartz

1. Values are unmistakably linked to emotions and moods. When values are activated, people become infused with feeling. People who value freedom become aroused if their independence is threatened, act with despair when they are helpless to protect it, and are happy when they can enjoy it.

2. Values direct us to desirable goals that motivate action. Values move us to take action. People who hold social order, justice, and helpfulness as important values are motivated to pursue goals that express these values.

3. Values transcend specific actions and situations. The values of obedience and honesty, for example, are relevant in many different situations, and useful in the workplace or school, in business or politics, with friends or strangers. This distinguishes values from norms and attitudes that are only useful for specific actions or in certain situations.

4. Values serve as standards or criteria. Values guide the selection or evaluation of actions, policies, people, and events. People decide what is good or bad, justified or illegitimate, worth doing or avoiding, based on possible consequences for their cherished values. But the impact of values in everyday decisions is rarely conscious. Values enter awareness when the actions or judgments one is considering have conflicting implications for different values one cherishes.

5. Values are ordered by importance relative to one another. People’s values form an ordered system of priorities that characterize them as individuals. Do they give more importance to achievement or justice, to novelty or tradition? This hierarchical feature also separates values from norms and attitudes.

6. The relative importance of multiple values guides action. Any attitude or behaviour will often impact more than one value. Competing values will guide attitudes and behaviours that allow for trade-offs. If you value self-discipline for achievement more than stimulation, you will sit down and work instead of going to the party. Values influence action when they are relevant and important to the actor.

Rokeach Value Survey

Another social psychologist, Milton Rokeach, developed a Value Survey to collect large amounts of data, and he published his findings in a number of books, including Understanding Human Values. created the Rokeach Value Survey. This core values list consists of 36 values, split into two groups. The first group, Terminal Values, represent what people seek. The second group, Instrumental Values, represent the way people want to live.

ViDA does not ascribe to Rokeach's full definition, as values are not goals.

Terminal Values

Terminal values are end-states that people like to have. According to the ViDA definition of values, these are means values or ideals that motivate us to live our core values. Speaking to these universal values can also help you connect with others more effectively.

- True Friendship

- Mature Love

- Self-Respect

- Happiness

- Inner Harmony

- Equality

- Freedom

- Pleasure

- Social Recognition

- Wisdom

- Salvation

- Family Security

- National Security

- A Sense of Accomplishment

- A World of Beauty

- A World at Peace

- A Comfortable Life

- An Exciting Life

Instrumental Values

Instrumental values are ways of behaving that people prioritize. According to the ViDA definition of values, these are categories of core values.

- Cheerfulness

- Ambition

- Love

- Cleanliness

- Self-Control

- Capability

- Courage

- Politeness

- Honesty

- Imagination

- Independence

- Intellect

- Broad-Mindedness

- Logic

- Obedience

- Helpfulness

- Responsibility

- Forgiveness

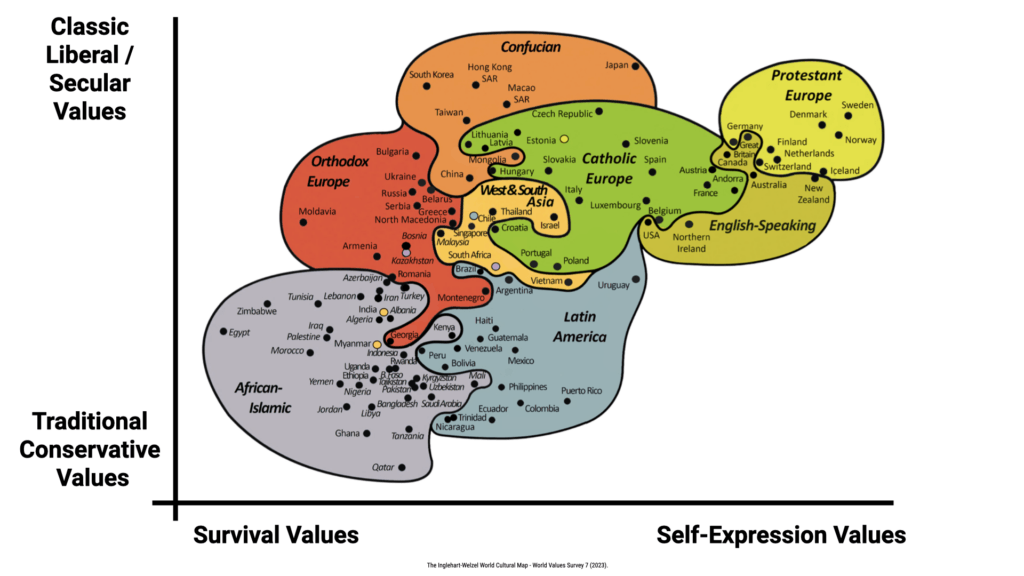

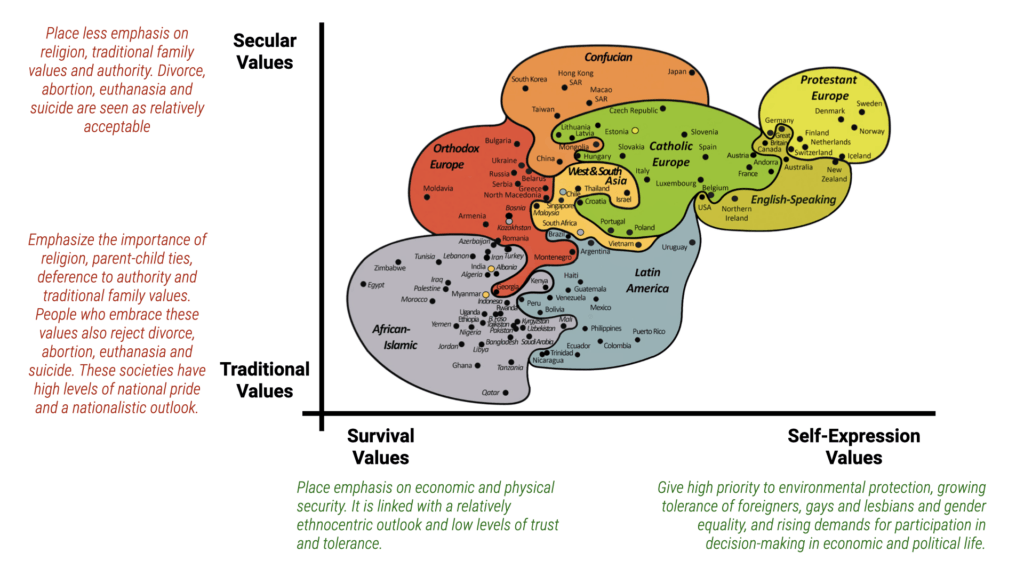

World Values Survey

The World Values Survey (WVS) is an international research program devoted to the scientific and academic study of social, political, economic, religious and cultural values of people in the world. At the moment, WVS is the largest non-commercial cross-national empirical time-series investigation of human beliefs and values ever executed.

The world values survey classifies different cultural values that are being expressed, then compares different national societies with each other.

Inglehart–Welzel Cultural Map

The following map was created by political scientists Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel to better understand how to direct social and economic development. You will see two dimensions of social values compared to one another:

- Traditional values plotted against Secular-rational values on the Y-axis

- Survival values plotted against Self-expression values on the X-axis

Traditional values

These emphasize the importance of religion, parent-child ties, deference to authority and traditional family values. People who embrace these values also reject divorce, abortion, euthanasia and suicide. These societies have high levels of national pride and a nationalistic outlook.

Secular-rational values

These values are defined by what they are not. Secular-rational values have preferences opposite to traditional values. These societies place less emphasis on religion, traditional family values and authority. Divorce, abortion, euthanasia and suicide are seen as relatively acceptable.

Survival values

These values place emphasis on economic and physical security. Survival values underpin an ethnocentric outlook and low levels of societal trust and tolerance.

Self-expression values

This group of values gives high priority to environmental protection, tolerance of foreigners, gay, lesbian and gender equality. This group demands more participation in decision-making in economic and political life.

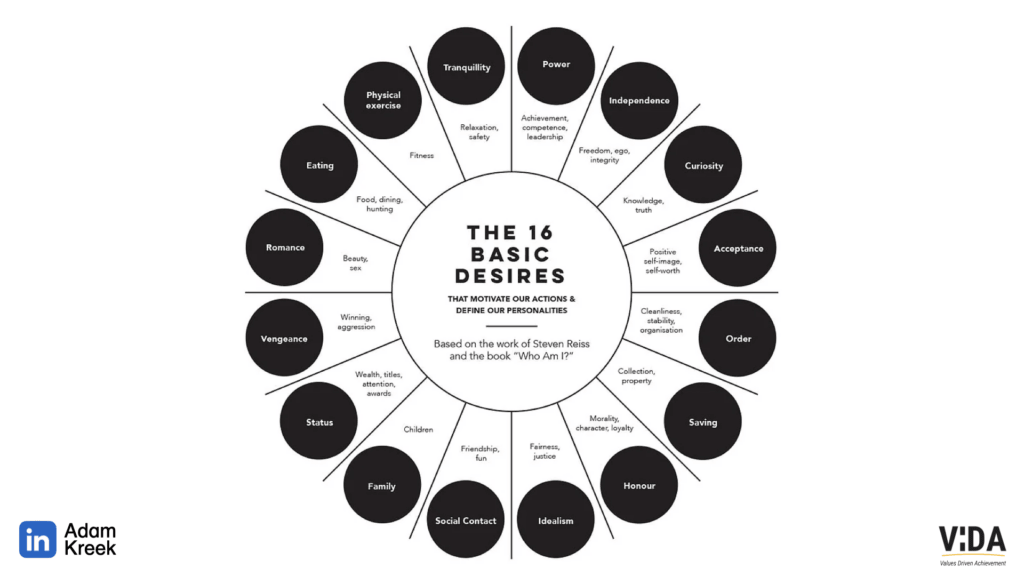

16 Desires of Motivation

Starting from studies involving more than 6,000 people across the globe, Professor Steven Reiss proposed a theory that find 16 basic desires driving almost all human behaviour. These intrinsic desires directly motivate a person's behavior, and do not satisfy other desires indirectly.

Some of these values are terminal, and some are instrumental. Reiss's index can help to inform actions we need to take, or outcomes we need to move towards to achieve our ideal values state.

The desires are:

- Acceptance, the need for approval

- Curiosity, the need to learn

- Eating, the need for food

- Family, the need to raise children

- Honor, the need to be loyal to the traditional values of one's clan/ethnic group

- Idealism, the need for social justice

- Independence, the need for individuality

- Order, the need for organized, stable, predictable environments

- Physical activity, the need for exercise

- Power, the need for influence of will

- Romance, the need for sex

- Saving, the need to collect

- Social contact, the need for friends (peer relationships)

- Status, the need for social standing/importance

- Tranquility, the need to be safe

- Vengeance, the need to strike back or win

Dr. Reiss has since passed on, but his motivational profiling tool is still being used around the world.

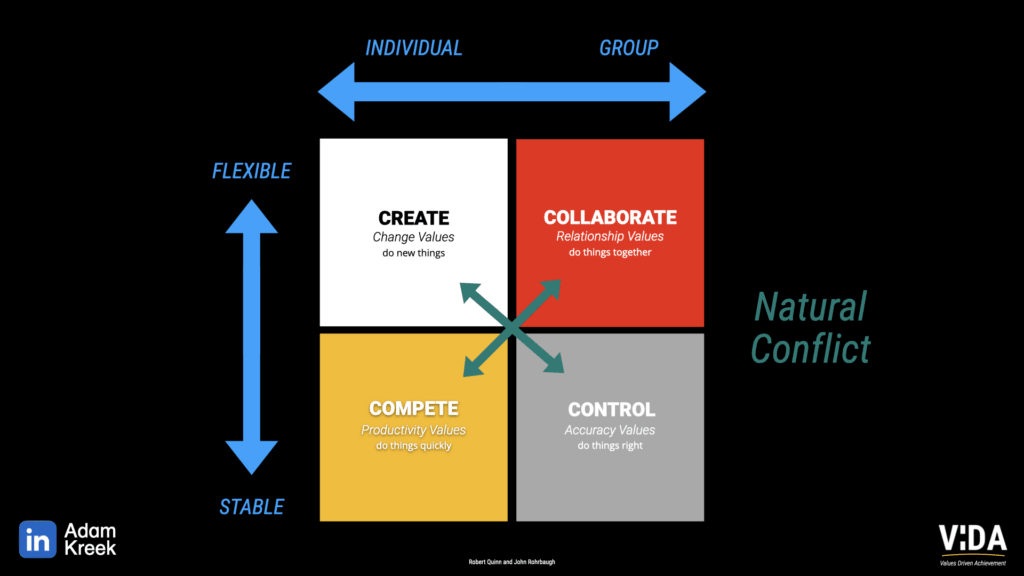

Competing Values Framework

The Competing Values Framework (CVF) is a powerful tool for understanding and improving organizational effectiveness. This method was developed by researchers Robert Quinn and John Rohrbaugh in the early 1980s. It helps leaders diagnose, understand, and navigate the complexities of organizational dynamics by identifying and balancing competing values within an organization. Here’s a concise breakdown of the framework and how it can be applied:

Four Quadrants of the CVF

- Collaboration (Clan Culture)

- Characteristics: This culture is like a family. It emphasizes mentorship, teamwork, and employee involvement. Leaders act as facilitators or mentors.

- Values: Commitment, communication, and development.

- Outcomes: High employee satisfaction, strong company loyalty, and collaborative environments.

- Creation (Adhocracy Culture)

- Characteristics: This culture is dynamic and entrepreneurial, focusing on innovation and agility. Leaders are seen as visionaries and innovators.

- Values: Flexibility, creativity, and risk-taking.

- Outcomes: High innovation, adaptability to change, and competitive advantage in new markets.

- Competition (Market Culture)

- Characteristics: This culture is results-oriented, emphasizing competition and achievement. Leaders are hard-driving producers and competitors.

- Values: Competitiveness, productivity, and goal achievement.

- Outcomes: High profitability, market share, and goal attainment.

- Control (Hierarchy Culture)

- Characteristics: This culture is structured and controlled, focusing on efficiency and stability. Leaders act as organizers and coordinators.

- Values: Consistency, efficiency, and formal procedures.

- Outcomes: High efficiency, stability, and reliable performance.

Read more about the CVF here.

Links to Schwartz's Theory of Values

At ViDA, we link the CVF to Shwartz's theory of values. It flips the diagram initially proposed by the CVF to reflect the underlying values conflicts that naturally occur on the Shwartz graph.

Barratts Values Inventory

Richard Barrett’s Values Inventory is a well-known framework that builds on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and integrates elements of Vedic philosophy to create a multi-tiered system for understanding personal and organizational values. Its unique contribution lies in its ability to foster greater self-awareness and alignment by identifying the motivators and aspirations driving individual and collective behaviour. However, the ViDA framework critiques Barrett’s model for conflating values with needs and motivators, such as labeling "family" or "health" as values, which ViDA identifies as external contexts or states rather than internal guiding principles. Despite this, Barrett’s methodology effectively increases personal and organizational awareness, making it a valuable tool for initiating deeper reflection and encouraging growth, even if its application could benefit from greater conceptual clarity.

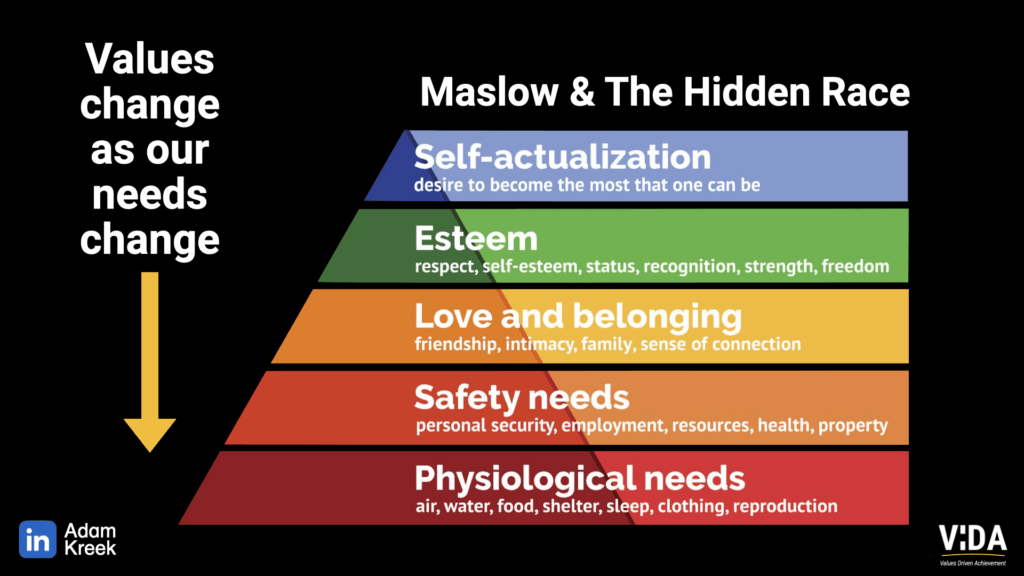

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs organizes human motivations into a pyramid, progressing from basic physiological requirements (like food and safety) to higher-order aspirations such as self-actualization. This model highlights how needs shift over time and context, as once a lower-level need is satisfied, attention often moves to the next. While ViDA’s values framework focuses on deeply held, stable character traits—such as integrity, authenticity, or compassion—it acknowledges that the way these values are prioritized or expressed may evolve as our needs change. For example, a value like courage might take precedence during times of uncertainty when survival is at stake, whereas creativity or growth may rise to prominence once stability is achieved. This dynamic interplay between needs and values illustrates how the two are connected yet distinct: needs drive immediate motivations, while values provide the guiding principles that influence how those needs are met.

The World Values Survey complements Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs by exploring how cultural and societal contexts influence the prioritization of values across populations. While Maslow’s model focuses on individual needs progressing from basic survival to self-actualization, the World Values Survey reveals how societal conditions—such as economic stability or existential insecurity—shape collective values, such as a focus on survival in unstable contexts or self-expression in prosperous, secure societies.

Schwartz’s Theory of Values that we saw above connects these perspectives by providing a structured taxonomy of universal values, such as benevolence, achievement, and security, that operate across cultures but are emphasized differently based on societal and individual circumstances. This interplay demonstrates that as societies or individuals address lower-level needs (like safety or sustenance), they often shift toward values reflecting higher-order priorities, such as creativity, autonomy, or altruism. Together, these frameworks illuminate how needs and values interact dynamically at both individual and societal levels, offering insights into human behaviour and cultural evolution.

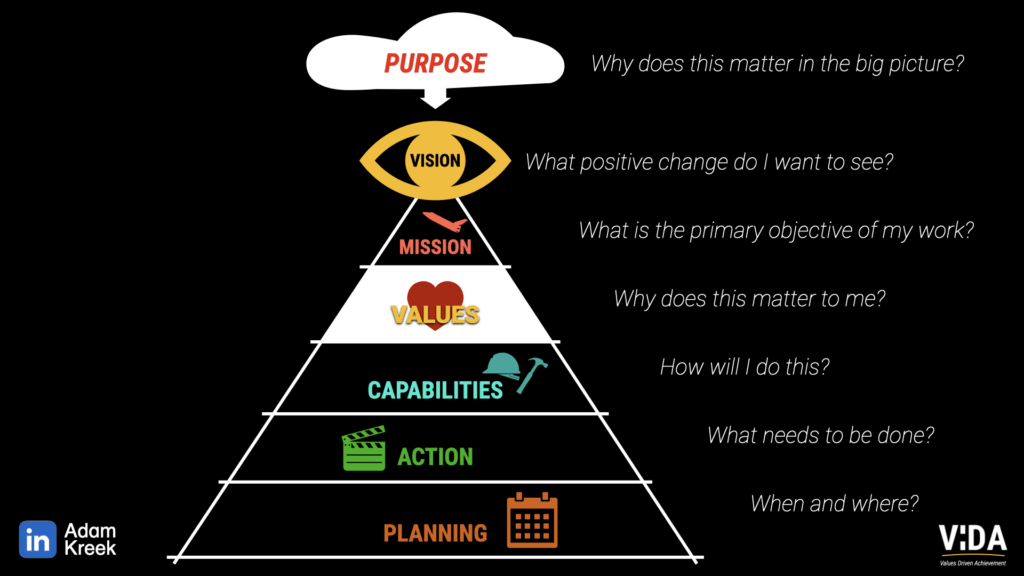

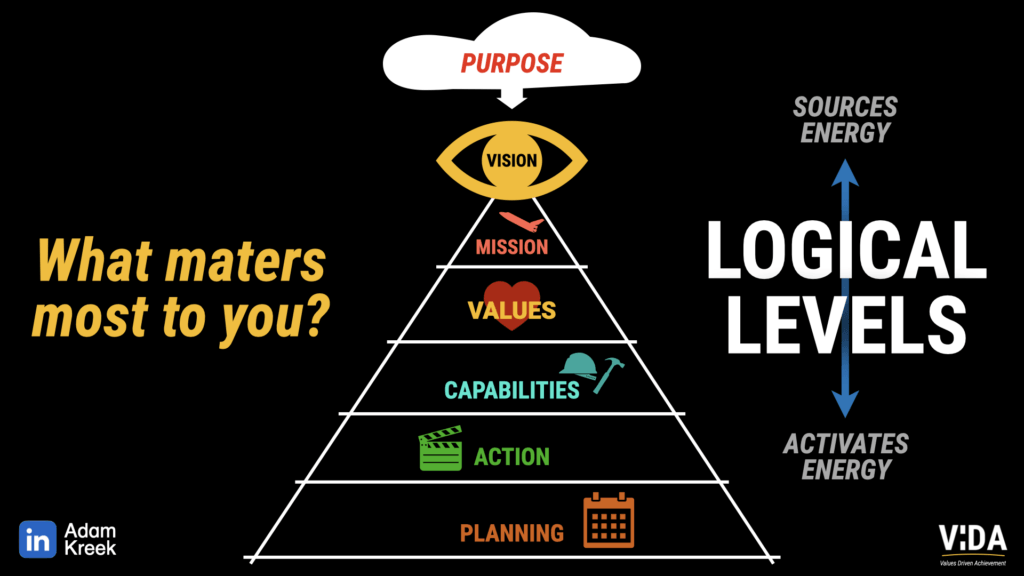

Logical Levels

Robert Dilts' Logical Levels model, also known as Neuro-Logical Levels, offers a hierarchical framework for understanding human experience and facilitating personal transformation. The model comprises six levels: Environment, Behavior, Capabilities, Beliefs and Values, Identity, and Spirituality. Each ascending level encompasses and influences those below it, suggesting that change initiated at a higher level can effect more profound transformation. For instance, altering one's Beliefs and Values can lead to shifts in Capabilities, Behavior, and interactions with the Environment. This structured approach aids in identifying the root causes of challenges and implementing effective interventions.

Integrating Dilts' model with the ViDA framework enhances the process of values identification and alignment. By examining the Beliefs and Values level, individuals can uncover core principles that drive behaviour and decision-making. Aligning these values with one's Identity ensures authenticity and coherence across all levels. Furthermore, recognizing how values influence capabilities and behavior enables targeted personal development and fosters growth that is congruent with one's foundational beliefs. This alignment facilitates personal fulfillment and enhances effectiveness in various life domains, as actions become a natural extension of deeply held values.